Something to look forward to: The semiconductor industry is in dire need of new workers and it is unlikely to find them in the United States. One possible solution has been proposed by the Economic Innovation Group, but can Congress come together on this sensitive issue in an election year?

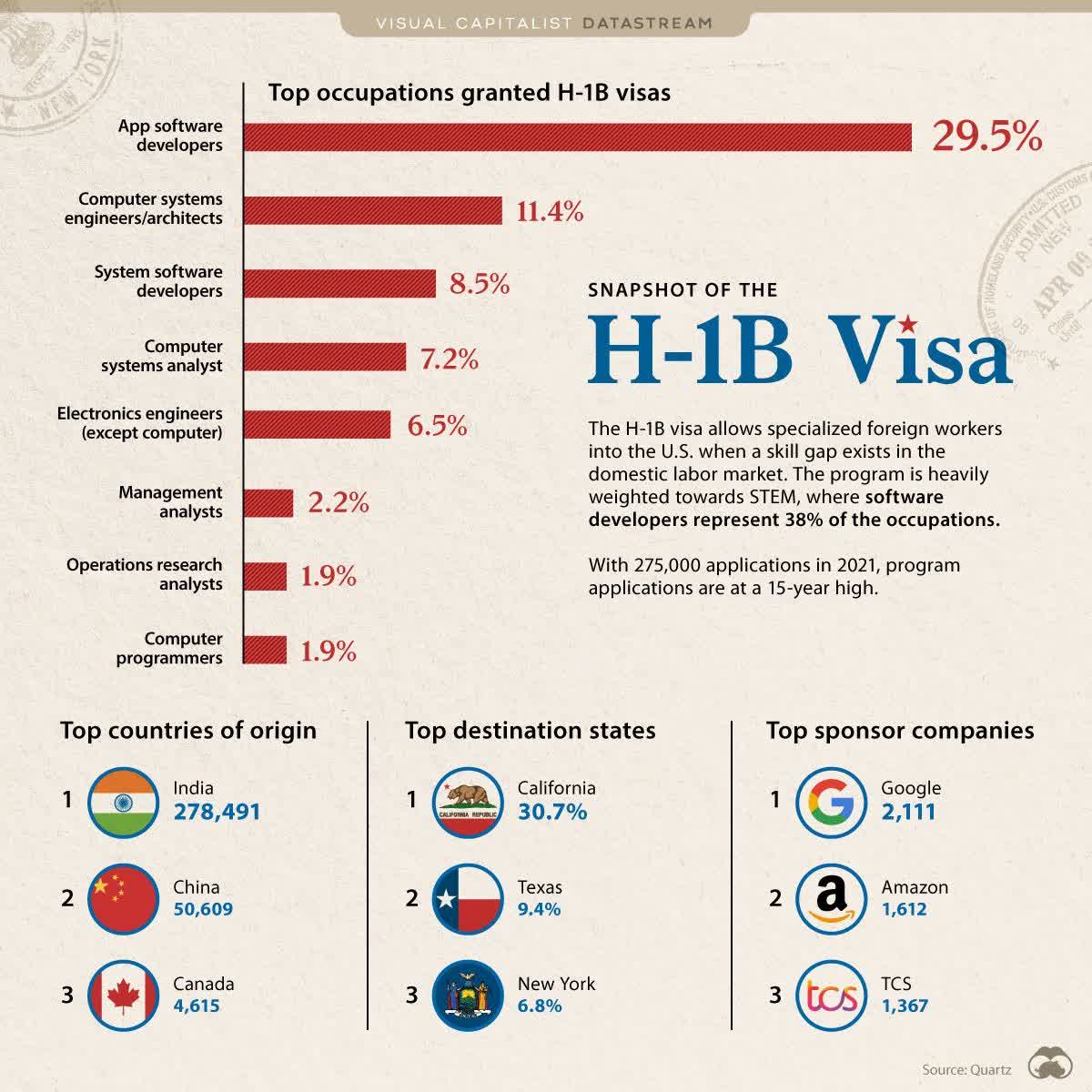

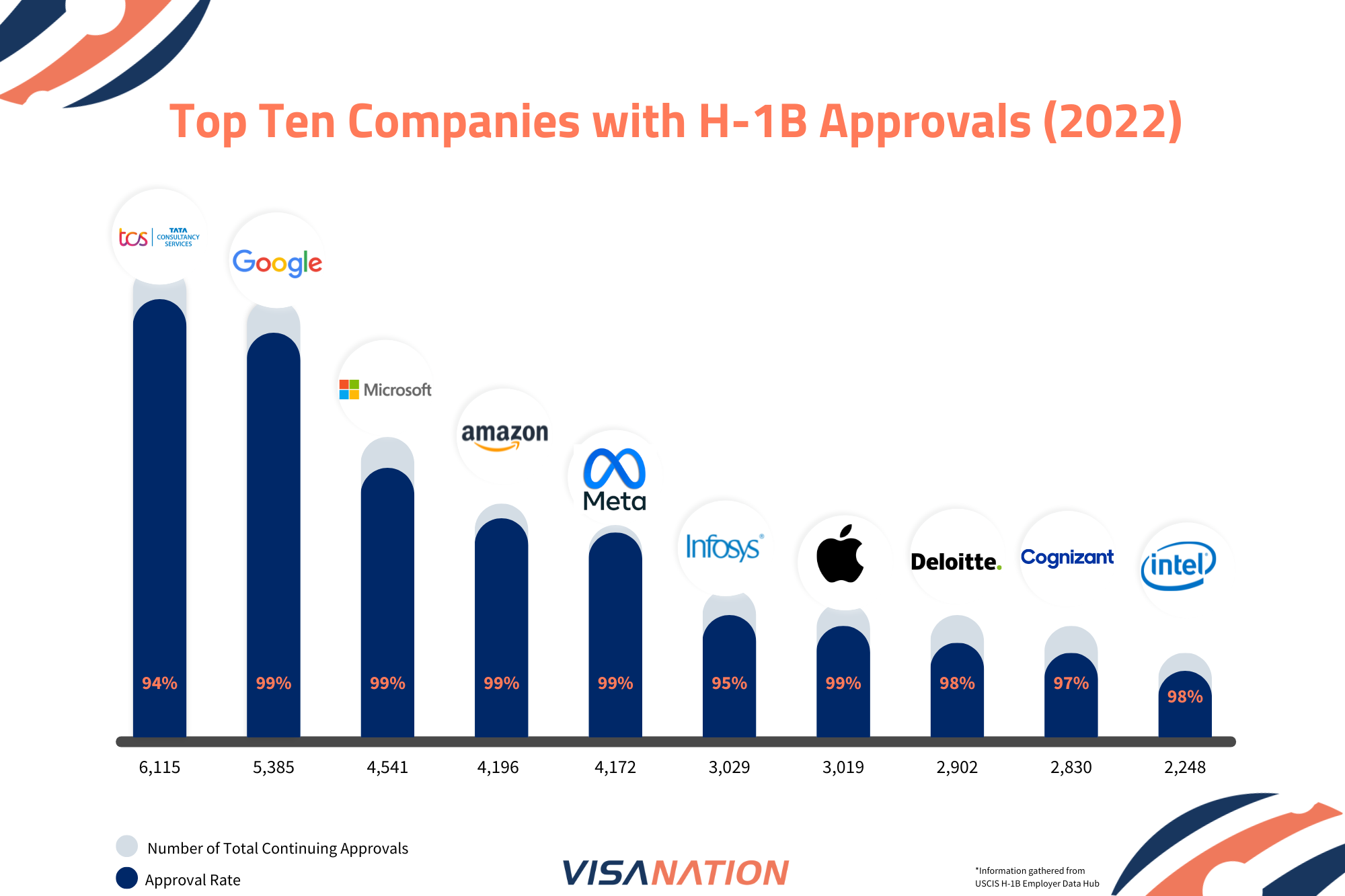

It is difficult to overstate the importance of the H-1B visa system to the US tech industry. American firms rely on it to bring in engineers, computer scientists, and technicians from foreign countries to do much of the advanced R&D and technical work they need to stay competitive. Americans work for these companies, too, of course, but their numbers don’t come close to meeting the industry’s needs.

Last year, the Semiconductor Industry Association and Oxford Economics released a study showing that the US is facing a projected shortfall of 67,000 of these specialty workers in the semiconductor industry by 2030, and a gap of 1.4 million such workers throughout the broader US economy.

But the H-1B program has its problems. It is a company-sponsored visa that is typically valid for three years and extendable to six. There is a 65,000 total annual cap on the visas, which are awarded by lottery tickets – a highly inefficient process that does not ensure they go to the best use, or to occupations of pressing national concerns, such as semiconductors, according to Adam Ozimek, chief economist at the Economic Innovation Group (EIG).

The system is also not easy to tinker with, at least politically. Critics of the H-1B visa say that it brings in foreign workers who are willing to work for less money than US workers, and that it is used by offshore outsourcing firms to replace US workers. Any discussion to ease some of its requirements usually leads to accusations that it will cost US jobs.

But the growing need for these workers, especially in the semiconductor industry, is prompting both the industry and the government to try and improve the process.

The US State Department recently announced a pilot program to allow eligible H-1B holders to renew their visas in the US instead of leaving the country. There had been a domestic renewal program in earlier years, but it was discontinued in 2004 over security concerns. But the scope of this pilot is limited as it is only open to current H-1B visas issued by Mission Canada from Jan. 1, 2020 through April 1, 2023 or by Mission India from Feb. 1, 2021 through Sept. 30, 2021.

Another solution offered by EIG details a more comprehensive solution. They have proposed a new Chipmaker’s Visa specifically for the semiconductor industry that would streamline the process by auctioning off 2,500 visas per quarter to qualified companies for a total of 10,000 per year with an expedited path to a Green Card. The visas would be good for five years and renewable only once.

EIG will be working to draft a policy this year with members of Congress who are interested in taking the lead on this, says chief economist Ozimek. There is hope that the idea could catch on; the CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 – which is generating even more demand for skilled workers in the US – was passed with broad bipartisan support.

On the other hand, this is an election year, and nothing will be easy to pass on highly polarized Capitol Hill. The Chipmaker’s Visa also has a branding problem – few in the government are talking about it, says Royal Kastens, director of public policy and advocacy at SEMI. “It’s hard to predict. There are certainly people on the Hill who would appreciate the idea. There are some who would have questions.”